Beginning to write about John Prine being gone before John Prine was actually gone is, in so many ways, an extremely John Prine thing to do. He’d surely find the humor in the ridiculous nature of having to prepare for the worst, and not because he was a cynic: but because he knew that searching for the wit, the absurdity, for that universal sigh of relief, was how we’d all get through whatever fate lobbed at us. Leonard Cohen once sang “there is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.” John Prine was that crack. He brought the light while never forcing us to forget the darkness. In moments like this, he’d surely want us to see both.

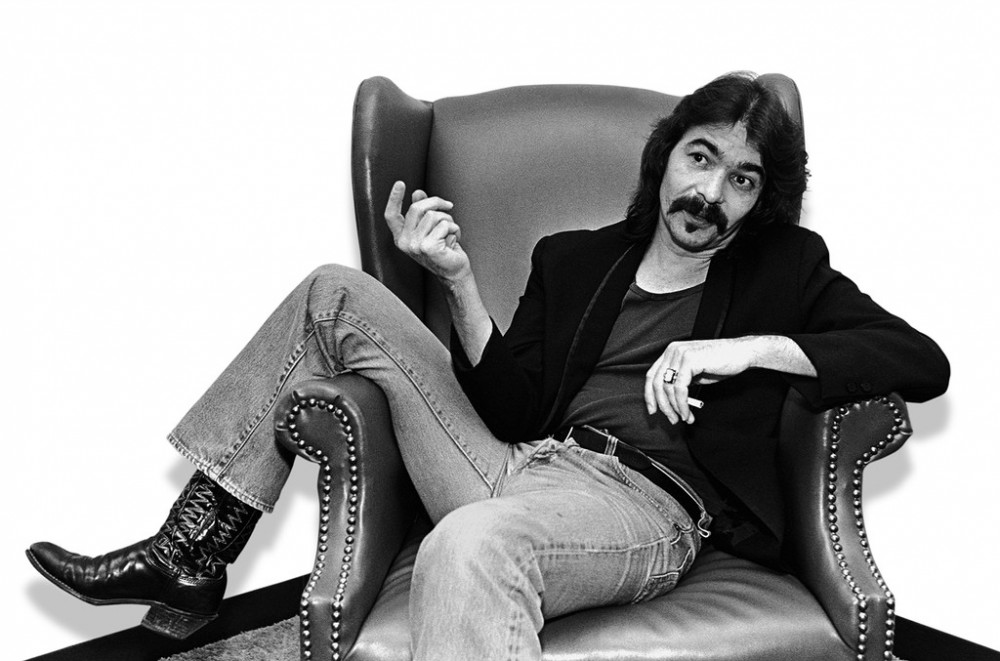

When news came that Prine, who died on Tuesday (Apr. 7) at 73, was battling COVID-19, we faced the impossible task of reflecting on who he was and what his music has meant to the world – a task growing far too common, with the passing of Adam Schlesinger, Joe Diffie, Ellis Marsalis and so many others far too soon from this relentless virus. I wondered how Prine, who had empathy for everyone from a melting snowman to poor Pluto — demoted from being a planet — might view a job like this: I could nearly picture him writing a ditty about a lonely reporter in quarantine typing obituaries and taking momentary solace in something small and beautiful just outside. Maybe a flower, a creaky screen door, a squirt of the right kind of mustard on a hot dog (because, according to Prine, there was a right kind).

Seeing the world though that lens was how he lived, and how he made music — his songs made you remember that love was as hilarious and imperfect as it was fulfilling, and that people were just people, doing the best they can. That the world was much more kind than it was cruel.

Prine painted his stories with the details that so few of us stopped to see — “Prine-isms,” you could call them, those quirky little tidbits that are especially missed in a world obsessed with the ephemeral. Other artists have tried for years to sing about the banal in the way Prine could, and most of them have failed: Prine never did it just for kicks, but because he saw the magic where most didn’t. He could sing about washing machines or eggs and make us appreciate their existence, or spin a metaphor around them. Prine loved words and language, but not in pretension – he delighted on a quirky phrase, a perfect syllable-to-beat match.

“Sometimes my old heart is like a washing machine, it bounces around ’til my soul comes clean,” he sang on “Boundless Love,” off of 2018’s The Tree of Forgiveness, his last record. “And when I’m clean and hung out to dry, I’m gonna make you laugh until you cry.” Few lines encompass Prine like that one does — that combination of perfect poetry with the mundane, that takeaway that kicks you in the gut. And, of course, that acute awareness of exactly what he did for us so often: make us laugh until we cry, cry until we laugh, a cathartic process that he could lead us in, like a preacher of the soul.

Prine became a legend in his lifetime, a patriarch and a collaborator at the same time: he wrote, sang and nurtured an entire generation of songwriters simply because he loved and believed in them, from Margo Price, Brandi Carlile, Jason Isbell, Amanda Shires to Sturgill Simpson, Tyler Childers and his label, Oh Boy’s, newest signings, Kelsey Waldon and Tre Burt. He was one of those artists whose work grew more vital, and more necessary, as he got older, because we needed his kindness, his attention to the details that surround the moments and spaces that time, stress or an Instagram story would forget. He grew while remaining stunningly consistent – the reinvention in his music came in new words, not experimental sounds.

But he always remained approachable, too: He held the launch party for The Tree of Forgiveness at a dive bar pool hall in Nashville — because that’s where he liked to go, so what’s the use of being fancy for fancy’s sake? He notoriously kept Christmas trees up year round, for the sheer joy of it, and sent them to friends and collaborators as gifts. He ate lunch every Tuesday he could at Arnold’s Country Kitchen because he enjoyed the meatloaf there, even after word got out: Prine would never hide from fame in that way because he didn’t write or exist to be above the world, he wrote and existed to be part of it. He loved his wife and his family with a warmth you could see and feel; enormous, boundless and true. If you lived in Nashville, you might have run into Fiona or his son Jody at a show, and they would say hello like old friends – part of the community, how they all liked it.

Prine said he didn’t plan for The Tree of Forgiveness to be his last record, but, just in case, there’s a song at the end about exactly what he hopes heaven will look like when he got there, called “When I Get to Heaven”: all the cigarettes he can smoke, all the cocktails he can drink, all the loved ones he might see again when he’s gone. Even the parasitic critics he might allow to tag along. He’s surely there now, smoking a cigarette nine miles long. “When I get to heaven, I’m gonna take that wristwatch off my arm,” he sang. “What are you gonna do with time after you’ve bought the farm?” Even in the worst times, like now, it’s impossible not to laugh and cry, all at once, at such a line. What relief it gives us. What relief, John Prine gave us, and will continue to give. He was in on the joke all along, in this thing called life.

39

39